Buckley’s Self-Discovery Takes Him Within Sight of the Holy Grail

Sep, 2018

Perhaps the first sign of a shift in Nathan Buckley’s approach – to himself, as much as to his players and staff – came in October last year when the coach went to Bali with his wife to practice yoga and meditation.

Buckley and wife Tania went with Luke Darcy and his wife Bec to “Sukhavati Bali”, near Seminyak, where Darcy had purchased an old Buddhist retreat that had belonged to the former Seeker, Bruce Woodley and turned it into a venue for yoga and Balinese relaxation.

If the Buckleys often take holidays in October, that he was doing yoga and meditation while the Magpies were ensconced in the trade period might be viewed, retrospectively, as a sign of what would unfold in an extraordinary 2018, when the notoriously driven Buckley would “let go” – lightening the mood and the load on himself, creating a more relaxed and convivial environment for his players.

By the time of the Bali retreat, Buckley had survived an intensive review of the football department, as Eddie McGuire’s board – despite widespread reservations from most of them – accepted the recommendation from football boss Geoff Walsh that Buckley be retained, with certain provisos.

Buckley’s acute self-awareness – and willingness to embrace change – shone through in this vexed and painful process, the candid coach having told the Collingwood board that he fought himself “every day” to allow people to do their jobs without interference.

“He’d want to know who was folding the towels,” said one staffer of the previous version of Buckley, noting the contrast with the willing delegator of 2018.

This weekend, as the Magpies play in their first grand final since 2011 – the last game before Mick Malthouse reluctantly handed the reins to the favourite son – the transformation of Nathan Charles Buckley, one of the most driven footballers of any era, has been the dominant story line at Collingwood, as the Pies have risen from 13th to within sight of the elusive grail that Buckley had pursued with such single-minded purpose as player and senior coach.

At 46, Buckley has spent precisely half of his life as player (14 years), assistant coach (two years) or senior coach (seven years) at Collingwood. But this year is the first time that he has harvested the benefits of stepping back, trying to do less rather than more, not sweating the small stuff, trusting others and recognising the limits of his influence.

The new defensive coach, Justin Longmuir, the architect of Collingwood’s successful method for defending this year, said: “I’ve really enjoyed working under him because he’s given us, given everyone autonomy to go about their jobs and that was from day one. I’ve really enjoyed that freedom.”

“He’d want to know who was folding the towels.”

-Collingwood staffer on Nathan Buckley, pre-2018

By not seeking the grail with such unrelenting zeal, it has come within touching distance.

It is telling that elements of this latest self-discovery are a reprise of Buckley’s playing days, when the champion learned to exercise restraint in dealing with less committed teammates.

As captain, Buckley had an epiphany when teammate Heath Scotland, then 20, told him: “When I talk to you, I feel like you’re thinking about the next thing you’re going to say to me, rather than actually listening.”

This time, the recognition was forced by failure as a coach, by the frank feedback he received via the Walsh review, and by his own capacity for self-analysis, a trait that his former football lieutenant and friend Neil Balme believes is Buckley’s greatest strength.

In the battle against his own voracious desire to command and control that he described to the club board, the “bearded” Bucks – lighter, more informal and jovial, more New Testament tolerant than Old Testament intolerant – appears to have won the day against the unrelenting version of the coach.

In 2018, Buckley has been influenced not simply by the directive of Walsh’s review, which told him to delegate more to his staff and to stop over-managing, over-analysing and generally overdoing it, but also by a book that encouraged him to take a more philosophical and accepting stance in his daily work.

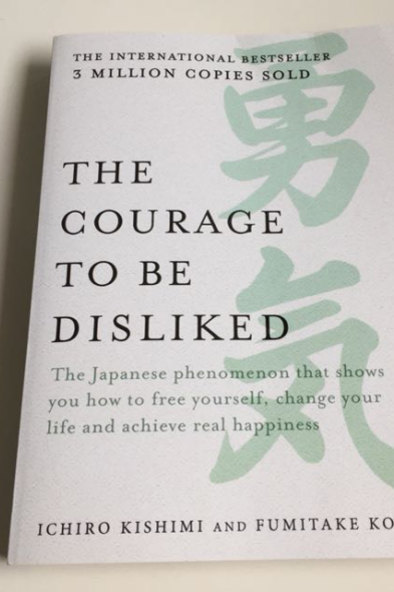

The Courage to be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga is a Japanese self-help guide that takes the form of a dialogue between a teenage student and a philosopher/mentor. In conversations with various parties, including the Collingwood players, Buckley has cited the book as a seminal influence upon his attitude this year.

One of the major themes from The Courage to be Disliked is that one cannot be overly concerned with what others think of you, or indeed, with what they decide to do with their lives. It encourages readers to be themselves, that they cannot please everyone and – crucially – that seeking recognition is an egotistical trap.

The book, while Japanese, draws on the popular theories of famed 19th century Austrian psychotherapist Alfred Alder, who founded the concept of “individual pyschology”.

During a pre-season camp on the Gold Coast this year, Buckley mentioned in passing his own 2008 book, All I Can Be, a searingly candid account of his struggles to become a champion footballer in which the most interesting subplot is how the young Bucks was shaped largely by his overbearing and hard-marking father Ray. Yet All I Can Be, as Buckley told one person at the Gold Coast camp, was another example of something he’d done in the past to gain recognition and feed the ego.

Conversations with players this year have been less footy-focused, in fact. Buckley has taken a more holistic view, showing warmth and care for players as people first before critiquing their kicking or craft.

In an annual mid-season seminar that Collingwood runs – and which is open to the public – Buckley also expressed a very different take in this year’s address. He told the gathering that the most important thing in the world was “connection with others”.

Buckley acknowledged at the coaches’ awards on Tuesday night (when he was named coach of the year, ahead of Adam Simpson) that he had learned something from Richmond’s embrace of “fun” in their program last year. But if part of the jovial tone has come from Garry Hocking’s jesting presence in the coaching panel, it’s also come from Buckley. Collingwood insiders cannot conceive of defender Lynden Dunn dressed up as a clown at training, as he was in a recent session, last year.

One of the striking features of this grand final week has been that, while many Victorians and people within the AFL universe retain that historic distaste for Collingwood, there is a far greater affection from the non-Collingwood public for Nathan Buckley.

Nathan Buckley and this year’s most famous footy beard

Why the fondness for a coach who was routinely booed as player? In part, the public can see someone who’s truthful, who has endured the slings and arrows of outrageous scrutiny and vitriol from fans and media (full disclosure: this scribe thought he should be sacked), who suffered from the Malthouse legacy, yet never succumbed to self-pity, anger or blaming others. In years past, he lost plenty of games, but never his dignity.

Some friends believe that the Buckley that we’ve seen in 2018 – the frank, warm and thoughtful middle-aged man with a ginger beard – is much closer to the real Buckley than the man behind the stern, earnest mask.

“One thing I’ve never seen in him is arrogance at all,” said Walsh. “As a coach, I’ve never seen it (in him). He’s always been respectful of his fellow man.”

Walsh, like Balme, never wavered from his view that Buckley, with experience and one or two tweaks, would end up regarded as a good senior coach. “Just because of his honesty and his passion and he really wanted his players to be successful.”

In a sense, it had been Nathan Buckley’s intense craving for success that was almost his undoing. He wanted the grail too badly and couldn’t contain his zeal. This year, Buckley finally let go – and let the Magpies take flight.

Article featured in The Age.